Was a little-known standoff the real start of the American Revolution?

On February 26, 1775, residents of Salem, Massachusetts, banded together to force the British to withdraw from their town during an oft-overlooked encounter known as Leslie’s Retreat.

By Robert Pushkar, The Smithsonian – February 26, 2025

Seven and a half weeks before the “shot heard ’round the world” at the Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the conventional start of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775, a long-overlooked encounter between the British Army and the townspeople of Salem, Massachusetts, almost sparked outright war. At a river and over a bridge, American colonists’ desire for independence reached a fever pitch as they stood their ground against the distant kingdom of their heritage.

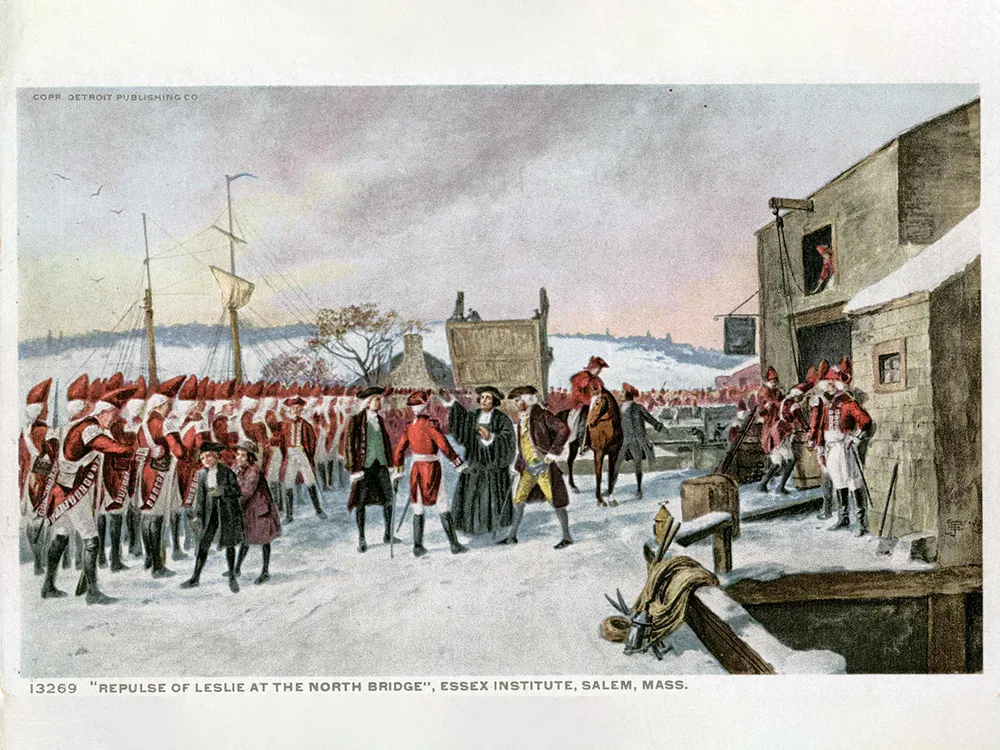

Known as Leslie’s Retreat, the standoff took place on February 26, 1775, when British Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Leslie led a raid to seize suspected cannons from a makeshift Colonial armory in Salem. Instead of finding artillery, Leslie encountered an inflamed citizenry and militia members ready to stop his search. These colonists flooded Salem’s streets, preventing Leslie’s passage and forcing him to negotiate. Ultimately, the Salemites convinced the British Regulars to stand down and return to Boston. No shots were fired, and no one was seriously injured—aside from the boundless pride of the British occupiers.

Had Charles Moses Endicott, a retired sea captain and Salem’s unofficial town historian, not taken it upon himself to publish an 1856 text about the failed raid, it might have been lost to history. Called Account of Leslie’s Retreat at the North Bridge in Salem, Endicott’s chronicle was based on eyewitness and secondhand testimony from elderly Salemites. Its title used the word “retreat” to reinforce overwhelming local sentiment about the circumstances of Leslie’s departure. “Here … we claim the first blow was struck in the war of independence, by open resistance to both the civil and military power of the mother country; comparatively bloodless, it is true, but not the less firm and decided,” Endicott wrote.

A scene from Salem’s 2025 re-enactment of Leslie’s Retreat | Robert Pushkar

To mark the 250th anniversary of Leslie’s Retreat, as well as the upcoming 250th anniversary of America’s founding on July 4, 1776, the city of Salem hosted a slate of commemorative events, including a re-enactment and a National Park Service exhibition. As Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo says, “The events of February 26, 1775, are of enormous historical significance for Salem and our nation. They reflect the resilience and strength of this community and of the colonists more broadly.”

–

A 1789 illustration of the Boston Tea Party, then known as “the destruction of tea at Boston Harbor,” by British engraver W.D. Cooper Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In the aftermath of the March 1770 Boston Massacre, the British Colonies in North America increasingly resembled a powder keg ready to explode. The bloodshed—five colonists killed and six wounded by British soldiers firing into a crowd—lingered in common memory. Three years later, in December 1773, Bostonians overtly rebelled, tossing more than 90,000 pounds of tea into the harbor in protest of the Tea Act, a transparent scheme to “seduce the colonists … into buying taxed tea, which would give up the principle of no taxation without representation,” Benjamin L. Carp, author of Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America, told Smithsonian magazine in 2023. These events sparked rebellious sentiments, adding to the colonists’ growing list of grievances against the British.

Even before the outbreak of war in 1775, General Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the British forces in North America, had his own network of spies, along with Loyalist sympathizers who gathered information on his behalf. One such individual was Benjamin Church, a physician and delegate to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. “Only a doctor could meet with a nonstop parade of people from all walks of life without creating suspicion,” writes historian Nathaniel Philbrick in Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution. “When asked why he socialized with so many Loyalists, [Church] claimed to be using them for his own political purposes.”

A depiction of British Lieutenant-General Alexander Leslie | Metropolitan Museum of Art

Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the British forces in North America | Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Church’s espionage reports were grave, indicating that colonists were readying “supplies for an army in the field, not a home guard,” writes historian Peter Charles Hoffer in Prelude to Revolution: The Salem Gunpowder Raid of 1775. Salem blacksmiths and barrel-makers were converting naval cannons for use on land, adding caissons (wheeled carriages) and supporting limbers to make the weapons stationary. Prior experience had taught Gage the superiority of these field artillery. Inaction was no longer a choice; Gage deemed action a necessity.

“Cannons could effectively block the passage of men over the narrow necks connecting peninsular port towns, like Boston and Salem, to the mainland,” Hoffer writes. Though Leslie’s Retreat is also known as the Salem Gunpowder Raid, Hoffer tells Smithsonian that “the raid was staged not looking for gunpowder, but rather for cannons.”

Gage dispatched Leslie, an experienced soldier and member of a high-ranking family of military elite, to lead the raid. A land march from Boston to Salem was out of the question. Sinuous coastal terrain, numerous inlets, jutting peninsulas and many harbors to maneuver through would be time-consuming and perilous. Instead, Gage ordered a sea route from Castle Island near Boston, where the British 64th Regiment of Foot was garrisoned. The soldiers would land at the coastal town of Marblehead, then continue on foot to Salem.

A 1775 map of the battles that took place in and around Boston. The town of Salem appears at top right. | Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Gage decided a Sunday raid would add an element of surprise, as he assumed most locals would be worshipping in church then. Little did he realize, however, that “it would be far easier for the militiamen to spread word of a British gunpowder raid at a few packed meetinghouses than it would during the week, when the male population was dispersed about the county or at sea,” Hoffer writes.

A predawn mist cloaked Massachusetts Bay early on February 26, adding to the numbing coldness. In darkness, the 64th Regiment boarded the HMS Lively, a frigate anchored as part of the British fleet that had blockaded Boston Harbor since June 1774. The detachment numbered an estimated 250 men, lightly dressed in white shirts and vests and scarlet coats with black trim. Expecting only a day trip, the soldiers left their greatcoats and bedrolls behind. They were armed with flintlock .75-caliber smooth-bore muskets and socket bayonets, and they carried waterproof cartridge pouches.

The voyage from Castle Island to Marblehead took nine hours. All of the men were hiding below deck to avoid being spotted by Paul Revere’s spy network, though the Patriot silversmith had already been tipped off about the impending operation. Cramped and freezing, the men huddled among smelly bilges and crawling vermin.

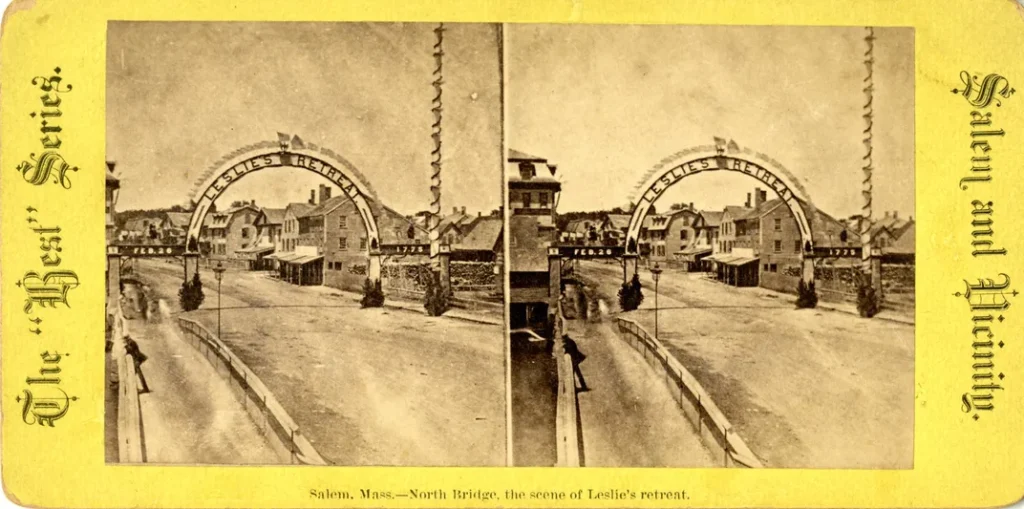

View of a triumphal arch commemorating Leslie’s Retreat on Salem’s North Bridge | Salem State University Archives and Special Collections under CC BY 2.0

Seeing the redcoats disembark at Marblehead, Major John Pedrick of the local militia mounted his horse and rushed to Salem to sound the alarm, much as Revere and two other riders would soon do in their famous midnight ride on April 18, 1775.

By midafternoon, sunlight and clouds alternated over Salem. Leslie approached the town “in an almost ceremonial manner,” Hoffer writes, and his regiment’s march “bore something of the aspect of a Sunday military parade.” Implicit in this approach lurked a calculated warning to onlookers not to resist the men’s progress.

Despite this warning, Salem’s church bells pealed, and drumbeats pounded out the alarm. Minuteman Colonel David Mason, who lived nearby, raced to the North Church and cried out, “The reg’lars are coming!” (Regular was a common synonym for redcoat at the time.) There was no mistaking the regiment’s mission, as the British soldiers carried lanterns, hatchets, pickaxes, spades, handspikes (bars used as levers) and coils of rope.

Congregants poured out of prayer services and filled the streets. Though colonists often carried concealed weapons to church, most were unarmed on the day of Leslie’s Retreat. Muskets were difficult to hide, and pistols were rare due to their high value. Thus, the 64th Regiment was never under serious threat.

The most direct entry to Salem was at the North Bridge, a small drawbridge that stretched over the North River. But a local, perhaps Mason, had pre-emptively ordered the bridge’s northern leaf raised to prevent the British troops’ progress.

Leslie gazed at the rowdy throng from across the bridge, doubting his plan to seize the rumored cannons. As Hoffer writes, “The colonials had almost certainly hidden the cannons and their carriages where, with what remained of the day, Leslie would never find them.” When asked to point the British to the artillery, prominent Salem businessman Richard Derby, who actually owned some of the weapons, retorted, “Find them if you can. Take them if you can. They will never be surrendered.”

A torrent of taunts, catcalls and fist-waving greeted the army. Rather than fire into the crowd, the British soldiers advanced with fixed bayonets. During the resulting scuffle, Joseph Whicher, a foreman at a nearby distillery, bared his chest, daring the soldiers to use their weapons. “Sufficiently pricked to draw blood,” according to Endicott, Whicher would later repeat his war story to anyone who would listen.

A float commemorating Leslie’s Retreat in a 1926 parade in Salem | Salem State University Archives and Special Collections under CC BY 2.0

Meanwhile, Minutemen from Salem and nearby Danvers stood armed on the northern bank of the river. Militia Captain John Felt shouted a threat for all to hear: “If you do fire, you will all be dead men.”

Leslie knew his troops had to cross the river to carry out his orders. To retreat was to risk disgrace. But Gage had made clear that his men should not resort to violence unless fired upon, and that their goal was to protect private property.

During the hour-and-a-half stalemate, patience wore thin on both sides. Leslie held brief counsel with his lieutenants, then told the onlookers, “I am determined to pass over this bridge before I return to Boston, if I remain here until next autumn.”

Tensions escalated. Had a soldier or a colonist gone rogue and fired their weapon, the American Revolution might have begun right then and there.

But locals wanted to avoid bloodshed. They had succeeded in hiding their weapons. They knew the enveloping darkness ensured that the British would never find them. Still, some among them understood that Leslie needed to save face.

An engraving of British soldiers entering Concord on April 19, 1775 | Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

An unexpected voice joined the fray. The Reverend Thomas Barnard Jr., a young Loyalist and minister, implored Leslie not to fire “upon these innocent people” and urged “that his troops might be restrained from pushing their bayonets.”

By then, night had fallen, and temperatures had dipped. Yet a desire not to irritate the troops tamped down the colonists’ pent-up resentment. The locals offered Leslie a way to save face, promising to lower the drawbridge and allow his regiment to “march in a peaceable manner” no more than 275 yards into the town, “and then return, without molesting any person or property,” Endicott wrote.

Leslie issued his orders, and the British soldiers marched to the other side, then halted and waited. After a pause, they wheeled around and retreated over the bridge, their fifes and drums competing with boisterous jeers. Near the end of their route, a nurse named Sarah Tarrant reportedly shouted from a nearby window, saying, “Go home and tell your master he has sent you on a fool’s errand and broken the peace of our Sabbath. What! Do you think we were born in the woods to be frightened by owls?”

Back in Marblehead, the regiment boarded boats and rowed out to the Lively in total darkness. They then sailed back to Castle Island. Leslie’s Retreat, writes Hoffer, “was not a victory of American troops over British troops. It was a victory of citizens claiming their own over the military doing its duty.”

–

On a bright April morning nearly two months later, British regiments marched in search of ordnance stored in the town of Concord, around 24 miles west of Salem. Though British commander in chief Gage had hoped to surprise the colonists, Revere’s midnight ride thwarted these plans, warning locals of the soldiers’ impending arrival. The American Revolution was about to begin.

The recent Salem debacle had been etched in Gage’s memory as he mulled over strategies to deal with American intransigence. But reliable intel about the storage of shot and cannons in Concord forced his hand, convincing him that an extreme show of force was needed to re-establish British authority. Known for his immense patience, Gage had not demoted Leslie following the lieutenant colonel’s retreat. Still, he chose Major John Pitcairn, one of Leslie’s subordinates, to lead the raid.

En route, the 700 or so British soldiers had to pass through Lexington, where they encountered two lines of colonist militiamen formed into a barricade across the green. The 70-plus men were led by Captain John Parker, a farmer who had fought in the French and Indian War.

While Leslie was more cautious and deliberative, Pitcairn was resolute. He ordered his troops to load their guns. Gage’s guidance still prevailed: No gunfire unless fired upon.

John Pitcairn falls into the arms of his son (center right) in this John Trumbull painting of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

But tempers flared as the British attempted to advance. During the chaos, a shot rang out, though historians continue to debate whether it was fired by a British soldier or a colonist. The crown had been challenged once again. Pitcairn ordered his troops to fire, killing seven militiamen and fatally wounding another. After the hysteria, smoke and shouting that followed, the British soldiers regrouped and continued on, veering west to travel the six miles to Concord.

They arrived three hours later and conducted their raid, finding three cannons. The rest of the weapons had been carried away and hidden. At the North Bridge, another showdown erupted as several British companies numbering 96 men confronted close to 400 militiamen from Concord and surrounding towns. The British opened fire, killing two militiamen, and the Patriots responded with their own volley, killing three British soldiers. Including losses during the British retreat, the death toll that day stood at 73 on the British side and 49 or 50 on the American side. The colonies were now at war with Britain.

Over time, the Salem standoff that preceded Lexington and Concord faded from memory. As Hoffer writes, events like the taking of Fort Ticonderoga, the siege of Boston and the invasion of Canada loom large in the popular imagination because they were connected to the men who would become the nation’s founding fathers. “Happenstance,” he adds, “left the protagonists at Salem behind.”

Still, as a prelude to the fight for independence, the bold, heroic actions of the colonists involved in Leslie’s Retreat—men and women who mobilized and stood together, defiantly risking everything to show that British power need not be invincible—are worth remembering. “Every potentially deadly confrontation that ends with a negotiated settlement,” Hoffer writes, “has a good ending—and provides a good lesson.”

TOP PHOTO: “Here … we claim the first blow was struck in the war of independence,” wrote Salem historian Charles Moses Endicott in his account of Leslie’s Retreat. | Salem State University Archives and Special Collections under CC BY 2.0

–

Robert Pushkar is a Boston-based writer, photographer, playwright and independent scholar in Hemingway Studies. His news articles, features and photographs appear in national and regional magazines and newspapers and online publications. His play, Martinis and Madness, premiered at the Boston Playwrights’ Theater Marathon 25.